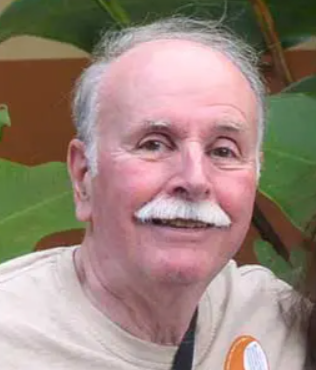

After the AALS conference in San Diego, I drove up to Los Angeles to spend a week with old friends I had not seen for more than 30 years. Two of them were my professors from Occidental College: Alan Chapman and Hal Lauter, Alan now teaches grad-level music theory courses at USC and hosts the morning program on its classical music station, KUSC, which is where I visited with him. Alan is as youthful as ever; still writing fun tunes and performing on occasion, sometimes with his entire family (btw, his son is a phenomenal mallet player). Hal Lauter taught me philosophy all the way through college, becoming my first intellectual mentor. He's 93 now but in great physical and mental condition.

Izabela was with me for the first few nights in LA. We stayed in Pasadena, in part because I remembered the town better than most other places in the LA basin. During my senior year of college, I had lived just up Lake St. in Altadena. Seeing that old house again brough back a lot of sweet memories. Izabela and I managed to get to the Norton-Simon museum, the Huntington Library, Museum and Gardens, and the campus of Occidental College. I was very happy to see that, despite inevitable changes, the Oxy campus felt as it did when I was a student there more than 40 years ago.

The morning after we arrived in Pasadena, we had brunch with my college roommate for two years, Jim Kerman and his wife Cathy. I don't have enough adjectives to describe what it was like being "Kermo's" roommate, so I'll just use one, awesome. We actually became friends when I was a freshman and he was a sophomore. A group of us - the "Late-night Munch Bunch" - included, in addition to Jim and me, Shelly Williams, Deirdre Mulligan, and Gail Fiattarone. Gail stayed a close friend of ours throughout college, but Jim and I lost touch with her after graduation.

After a couple of days, Izabela grabbed a flight to the Bay Area to visit an aunt in Walnut Creek and then flew down to Palm Springs to visit another aunt. After she left, I moved in with my other best friend from college, Peter Marston, who lives on the Western edge of Glendale, near Burbank. Peter is a professor of Communication Studies at Cal State Northridge. Unlike me, he still loves teaching and plans to do it until he drops. Also unlike me, he's never stopped writing, recording and performing music. His status in the LA pop-rock scene is at this point almost legendary. I stayed with him for four nights and it was so great to confirm just how much we were alike, but also how much we enjoyed disagreeing. Peter organized outings to a couple of great used-record stores, which created problems for me when I was packing to head home. We also visited the Grammy Museum at LA Live, had lunch with another college friend (and musician) Nate Haase, and had a memorable dinner at Jim Kerman's house in La Crescenta.

One day, Peter and I drove down to Coronado Island to spend some time playing music with another old friend, George Sanger. George is famous in the video game world for being one of the pioneers of video game music composition and production. I even recall seeing a Wall St. Journal profile of him several years ago. These days, he seems quite content living on the island in the house he grew up in with his wife Cindy. Having a chance to play some tunes with Peter and George again was pretty magical. The last time we had played together was at the Troubadour in LA in 1980.

I also had the chance, during the visit, to spend more than an hour catching up with another dear friend from college, Matt Walker, in his office at Disney Animation. Matt's Senior VP for music at Disney Imagineering, which means he's in charge of all music for Disney Animation, Pixar, and the theme parks. Matt was actually the first musician I got to know at Oxy. He and I were both in the orchestra for a production of Godspell our Freshman year. And we kept playing together after the production ended. He's a great pianist in nearly all genres, though he says he doesn't get to play as much as he would like these days.

Importantly, the conversations with my friends were only partly about our shared experiences 40 years ago. We also wanted to brief each other on the highlights (and some lowlights) of our lives since then, and to learn about how life is for us now. Despite the length of time apart from these guys, they were all so easy to talk with, as if we had never been apart at all. As we all grow older, these old friendships seem to have enhanced importance. At least, they do for me.

The final few days of my trip were spent in the Coachella Valley with Izabela. In addition to visiting with her aunt and her uncle (who is unwell), we had a chance to revisit old haunts. Izabela and I met in Palm Springs in late 1988 and we were formally married in Palm Desert in 1990 (after an informal ceremony in a judge's chambers in Palo Alto a few months earlier). My grandparents had been wintering in Palm Springs since I was a teenager, and I would sometimes get to visit them there. Then, my mother and step-father moved to Palm Desert in the early 1980s, and remained there for about 10 years before moving to Scottsdale, AZ. While I was in law school ('84-'87) I would spend my summers and holidays in their house. It was there that I recouped for a month after donating a kidney in 1984. It was my favorite of our family houses. I thought it had been demolished long ago. So, it was a wonderful surprise to find it unchanged on this visit. I have so many memories of the place, mostly good ones.

All in all, it was a tremendous vacation. I planned to do no work at all during it, and for the first time in my adult life, I kept to that plan (after the AALS conference in San Diego, of course). The good it did me is immeasurable. And it wouldn't have happened if I were still teaching. Classes began in the law school on Jan. 11, and all my time up to then would have been spent on class preparation. Retirement has a lot to recommend it.